|

Data used in the analyses below (ecological condition, threat status, protection, distribution of activities, cumulative pressure from activities) are from the National Biodiversity Assessment 2018: Marine Realm Assessment. See the NBA 2018 website for access to the report.

|

EBSA Status Assessment and Management Recommendations

Ecological Condition, Threat Status, Current Protection and Key Features in the EBSA

Relevant Pressures and Activities (impact, extent) | Management Interventions Needed for the EBSA

Activity Evaluation Per Zone: Zoning Feasibility | Management recommendations for MPAs

Management recommendations for MSP | Research Needs & Future Process

EBSA report download | Back to the SA EBSA status and management home page

Tsitsikamma-Robberg is significant coastal area because it includes South Africa’s oldest MPA, with the conferred protection securing a particularly rich diversity including fragile (corals) and slow-growing (sparids) species. The EBSA also includes several priority estuaries, which enhances its nursery function, and supports numerous bird species. Many threatened species occur here, including an Endangered endemic seahorse.

Click here for the full EBSA description

[Top]

Tsitsikamma-Robberg has a myriad of features and ecosystem types that need to be protected for the area to maintain the characteristics that give it its EBSA status. The criteria for which this EBSA ranks highly are: importance for life history stages, importance for threatened species and habitats, vulnerability and sensitivity, and biological diversity. There are 19 ecosystem types represented, many of which contain fragile, habitat-forming species that are especially sensitive to damage, as well as slow-growing species, like sparids. There are also many threatened species and some threatened ecosystem types in the EBSA, from the Endangered endemic seahorse to some of the abundant top predators (sharks, cetaceans and marine mammals). The five largest estuaries in the EBSA support important life-history stages of many species.

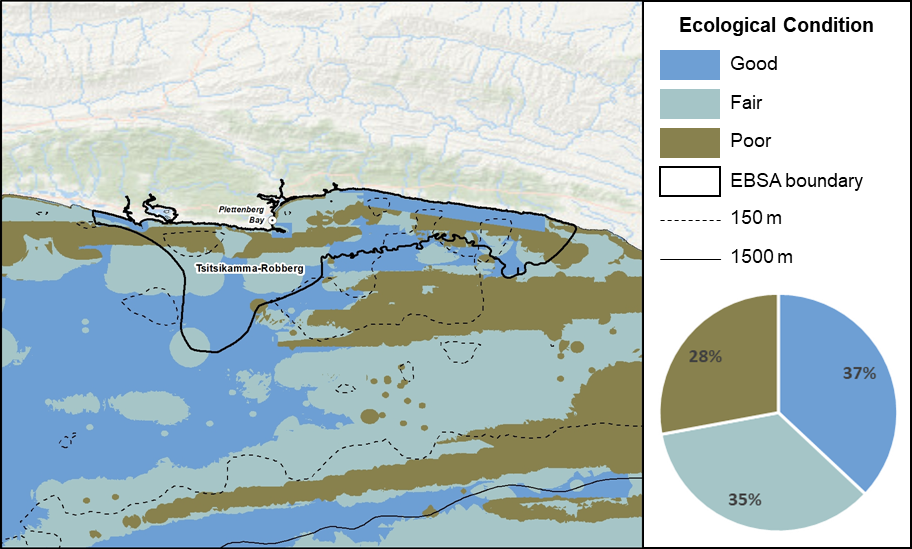

Tsitsikamma-Robberg proportion of area in each ecological condition category.

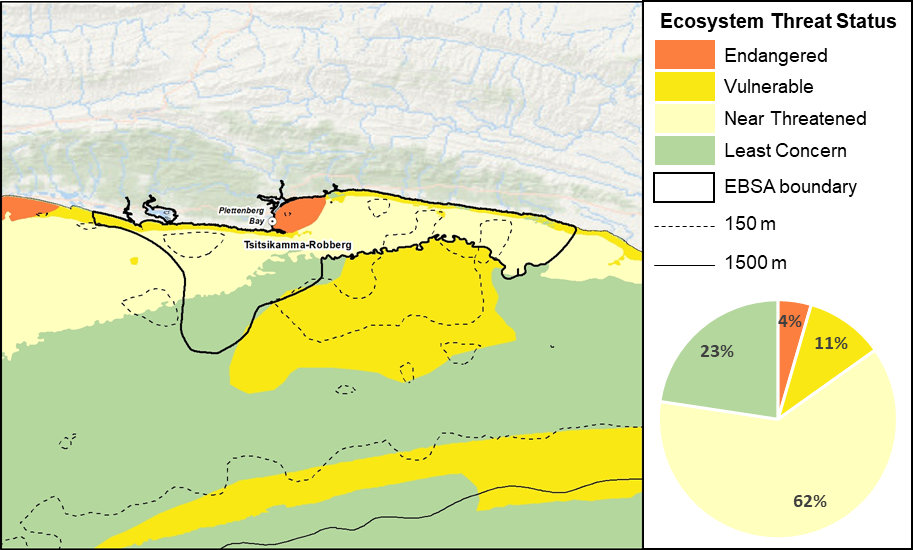

Ecological condition in Tsitsikamma-Robberg is split roughly equally among the three categories: 37% good, 35% fair and 28% poor ecological condition. Consequently, the bulk of the EBSA is Near Threatened (62%) or Least Concern (23%). However, the inshore areas, are more threatened; with 11% of the EBSA comprising Vulnerable ecosystem types, and 4%, Endangered ecosystem types.

Tsitsikamma-Robberg proportion of area in each ecosystem threat status category.

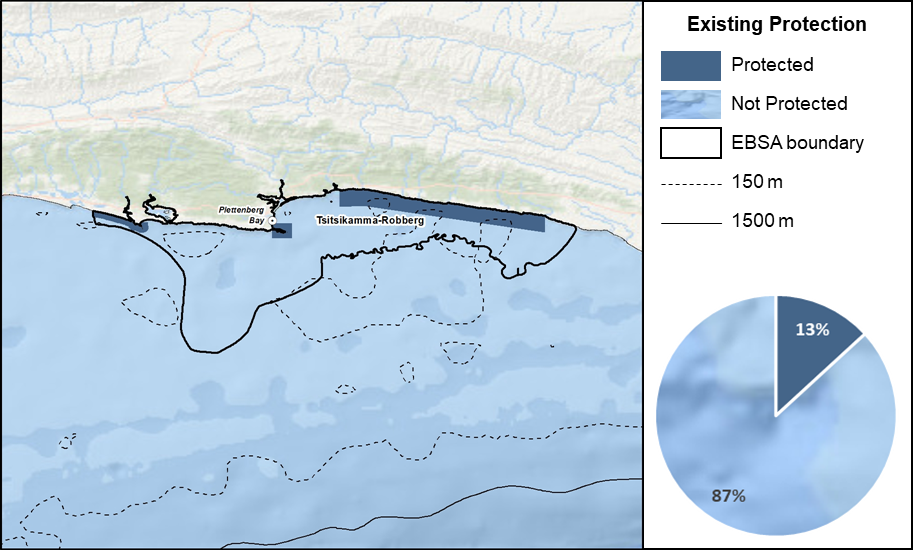

Tsitsikamma-Robberg proportion of area in a Marine Protected Area (MPA).

Protection of features in MPAs has not changed since the proclamation of the Operation Phakisa MPA network, with the EBSA area within reserves remaining at 13%. However, parts of Tsitsikamma MPA have been opened to recreational fishing, such that protection in some ways has declined in this area. Although many of the ecosystem types are well or moderately protected, there are still some that are poorly protected.

Threat status, protection level and ecological condition of ecosystem types in the EBSA. Other key features are also listed.

|

Feature

|

Threat Status

|

Protection Level

|

Condition (%)

|

|

Good

|

Fair

|

Poor

|

|

Ecosystem Types

|

|

Agulhas Boulder Shore

|

NT

|

WP

|

26.0

|

74.0

|

0.0

|

|

Agulhas Dissipative Intermediate Sandy Shore

|

LC

|

WP

|

53.3

|

5.3

|

41.4

|

|

Agulhas Exposed Rocky Shore

|

VU

|

MP

|

25.1

|

63.3

|

11.6

|

|

Agulhas Inner Shelf Mosaic

|

VU

|

MP

|

46.4

|

31.6

|

22.0

|

|

Agulhas Inner Shelf Reef

|

LC

|

WP

|

52.4

|

40.7

|

6.9

|

|

Agulhas Intermediate Sandy Shore

|

LC

|

MP

|

83.4

|

1.3

|

15.3

|

|

Agulhas Mid Shelf Reef

|

VU

|

MP

|

47.5

|

52.5

|

0.0

|

|

Agulhas Mixed Shore

|

NT

|

MP

|

18.4

|

54.8

|

26.7

|

|

Agulhas Sandy Mid Shelf

|

NT

|

MP

|

29.6

|

31.3

|

39.0

|

|

Agulhas Sandy Outer Shelf

|

VU

|

PP

|

85.9

|

14.1

|

0.0

|

|

Agulhas Sheltered Rocky Shore

|

EN

|

MP

|

0.0

|

75.2

|

24.8

|

|

Agulhas Very Exposed Rocky Shore

|

VU

|

MP

|

11.4

|

81.0

|

7.6

|

|

Eastern Agulhas Outer Shelf Mosaic

|

LC

|

PP

|

59.7

|

37.9

|

2.5

|

|

Warm Temperate Estuarine Bay

|

VU

|

MP

|

15.3

|

10.0

|

74.7

|

|

Warm Temperate Large Temporarily Closed

|

VU

|

PP

|

90.0

|

0.0

|

10.0

|

|

Warm Temperate Predominantly Open

|

VU

|

PP

|

66.5

|

5.4

|

28.2

|

|

Warm Temperate Small Fluvially Dominated

|

LC

|

WP

|

86.7

|

13.0

|

0.2

|

|

Warm Temperate Small Temporarily Closed

|

LC

|

PP

|

8.1

|

78.1

|

13.8

|

|

Western Agulhas Bay

|

EN

|

PP

|

6.7

|

75.7

|

17.6

|

|

Other Features

|

-

Fragile and sensitive species that are slow growing, including both habitat-forming reef species, as well as animals such as sparids.

-

Boulder reefs that appear to be a unique ecosystem type in South Africa, supporting abundant carpenter, panga and giant octopus communities

-

Key populations of top predators, including Cape fur seals, sharks, seabirds and cetaceans, including sites for feeding and breeding (e.g., Southern right whale breeding area, and a breeding colony of Cape fur seals at Robberg)

-

Most of the EBSA is backed by the terrestrial Garden Route National Park, and it forms part of the much larger Garden Route Biosphere Reserve

-

Tsitsikamma-Plettenberg Bay Important Bird and Biodiversity Area, within which at least 300 species of birds have been recorded

-

Endemic Endangered seahorse

|

[Top]

-

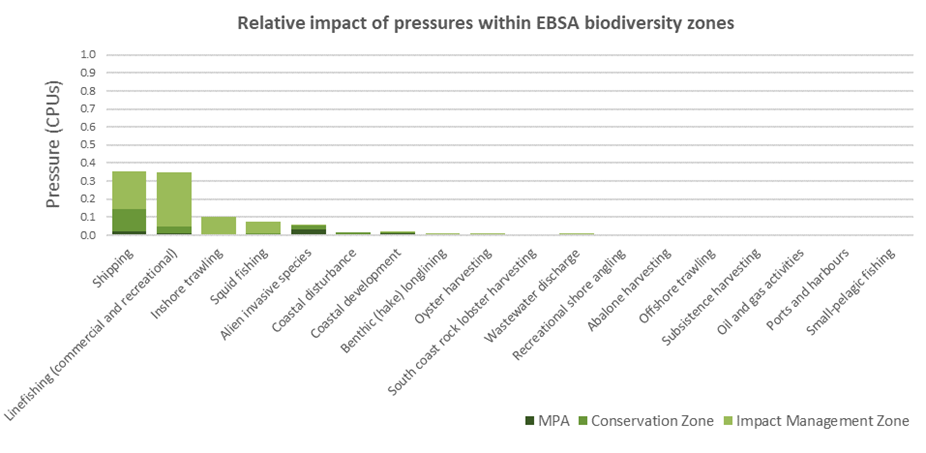

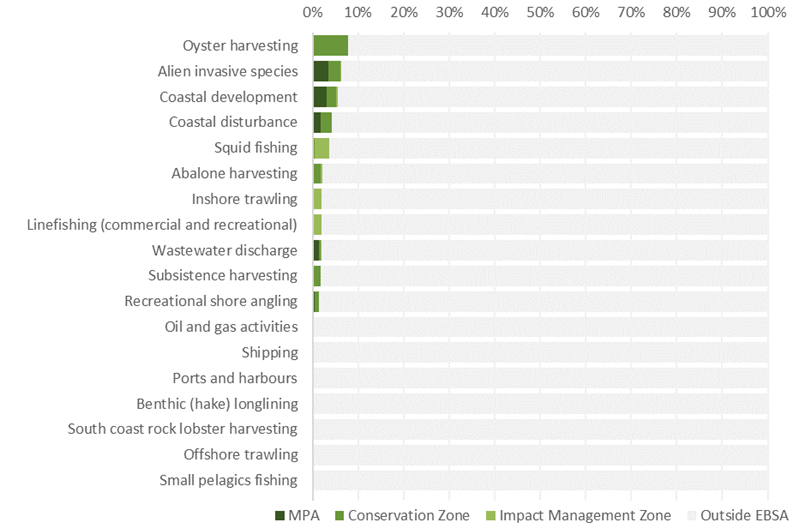

There are 18 pressures present in this EBSA, of which shipping is the only one that covers the entire EBSA extent; however, linefishing has the highest cumulative pressure profile.

-

Key pressures in this EBSA that most directly impact the features for which the EBSA is described include: oyster harvesting, alien invasive species, coastal development, inshore trawling, coastal disturbance, squid fishing, linefishing (commercial and recreational), abalone harvesting, wastewater discharge, subsistence harvesting, recreational shore angling, oil and gas (exploration and production), shipping, ports and harbours, benthic (hake) longlining, south coast rock lobster harvesting, offshore trawling, small pelagics fishing. These activities cover discrete portions of the EBSA, and are mostly concentrated in the shallower waters. These activities will need to be managed particularly well in order to protect the fragile benthic biodiversity and reefs, fish assemblages and top predators for which this EBSA is recognised. For most of these pressures, the larger portion of the activity is located in the Impact Management Zone.

-

Eleven of the 17 pressures each comprise <1% of the EBSA pressure profile, including: benthic (hake) longlining, south coast rock lobster harvesting, oyster harvesting, wastewater discharge, offshore trawling, abalone harvesting, recreational shore angling, subsistence harvesting, oil and gas (exploration and production), ports and harbours, and small pelagics fishing. Note that some of these are coastal pressures, and despite comprising a small extent of the EBSA, can overlap with and impact substantial portions of the small-extent ecosystem types in which they occur, e.g., shore-based recreational fishing.

-

Activities in South Africa that are not present in this EBSA include: beach seining, dredge spoil dumping, gillnetting, kelp harvesting, mariculture, mean annual runoff reduction, midwater trawling, mining (prospecting and mining), naval dumping (ammunition), pelagic longlining, tuna pole fishing, prawn trawling, shark netting, west coast rock lobster harvesting.

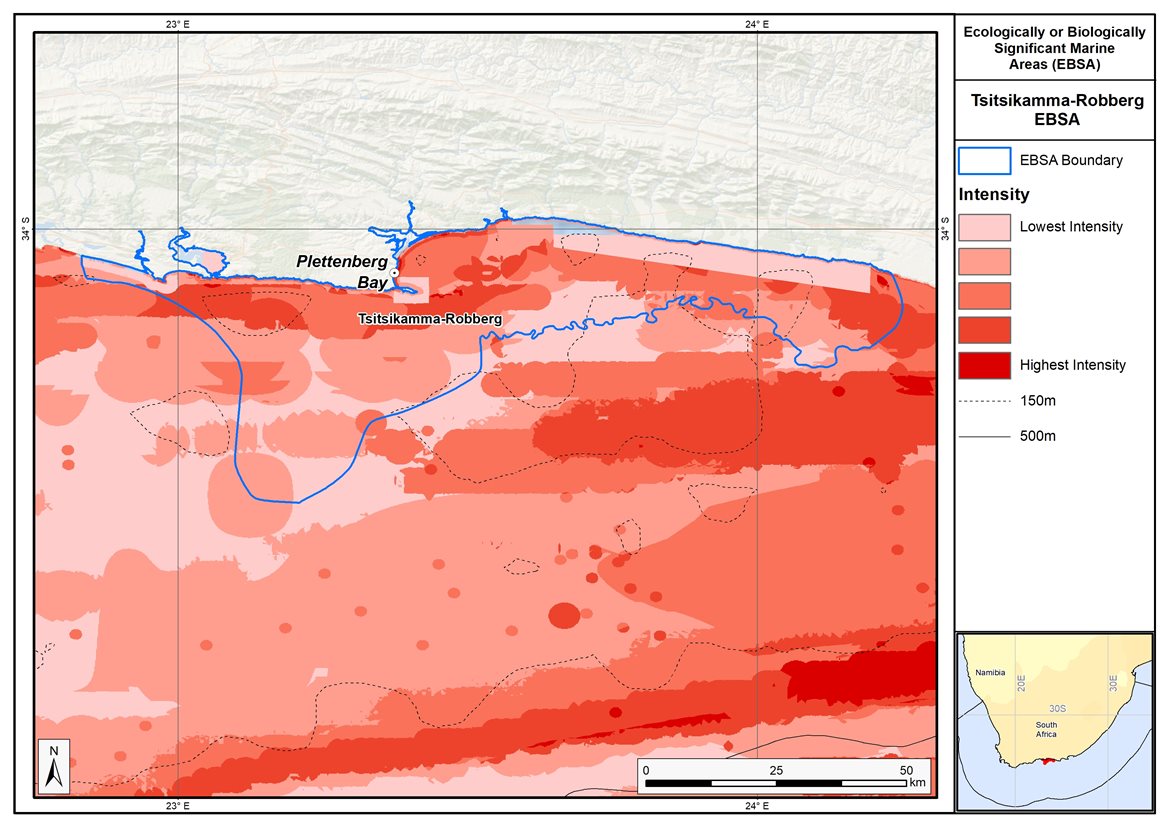

Map of cumulative pressure from all activities in the EBSA and surrounds. Darker reds indicate higher pressure intensity.

Pressure (in arbitrary cumulative pressure units, CPUs) summed for each pressure in the EBSA, per proposed EBSA biodiversity zone, ranked left (highest) to right (lowest) by the overall relative importance of pressures in this EBSA. Note that pressures from coastal development to small pelagics fishing each comprise <1.2% of the EBSA pressure profile.

[Top]

Improved place-based protection of EBSA features should be pursued. In support of this, the EBSA is divided into a Biodiversity Conservation Zone and an Environmental Impact Management Zone, both comprising several areas within the EBSA. The aim of the Biodiversity Conservation Zone is to secure core areas of key biodiversity features in natural / near-natural ecological condition. Strict place-based biodiversity conservation is thus directed at securing key biodiversity features in a natural or semi-natural state, or as near to this state as possible. Activities or uses that have significant biodiversity impacts are incompatible with the management objective of this zone. If the activity is permitted, it would require alternative Biodiversity Conservation Zones or offsets to be identified. If this is not possible, it is recommended that the activity is Prohibited. Where possible and appropriate, the Biodiversity Conservation Zones should be considered for formal protection e.g., Marine Protected Areas or Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECM). The aim of the Environmental Impact Management Zone is to manage negative impacts on key biodiversity features where strict place-based measures are not practical or not essential. In this zone, the focus is management of impacts on key biodiversity features in a mixed-use area, with the objective to keep biodiversity features in at least a functional state. Activities or uses that have significant biodiversity impacts should be strictly controlled and/or regulated. Within this zone, ideally there should be no increase in the intensity of use or the extent of the footprint of activities that have significant biodiversity impacts. Where possible, biodiversity impacts should be reduced.

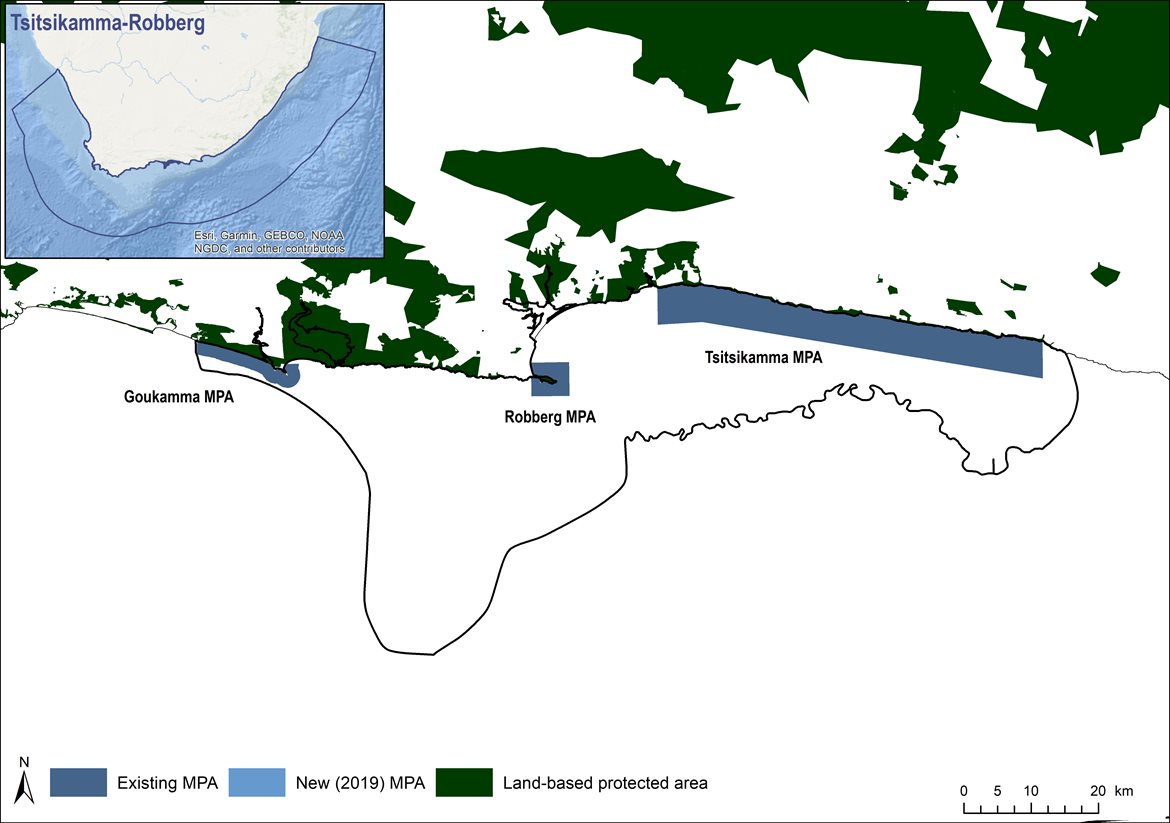

As far as possible, the Biodiversity Conservation Zone was designed deliberately to avoid conflicts with existing activities. There are also four MPAs that are wholly or partially within the EBSA: Goukamma MPA; Robberg MPA; and Tsitiskamma MPA. The activities permitted within these MPAs are not considered as part of the EBSA management recommendations because these are as per their respective gazetted regulations. Note that there are also several terrestrial Nature Reserves (including several privately-owned Nature Reserves) and the Garden Route National Park that are adjacent to the EBSA, and in some places, overlap with the estuarine area of the EBSA.

Proposed zonation of the EBSA into Conservation (medium green) and Impact Management (light green) Zones. MPAs are overlaid in orange outlines, with the extent within the EBSA given in dark green. Click on each of the zones to view the proposed management recommendations.

Protection of features in the rest of the Conservation Zone may require additional Marine Protected Area declaration/expansion. Other effective conservation measures should also be applied via Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) to ensure that the existing activities/uses are appropriately controlled to ensure compatibility of activities with the environmental requirements for achieving the management objectives of the EBSA Biodiversity Conservation and Environmental Impact Management Zones.

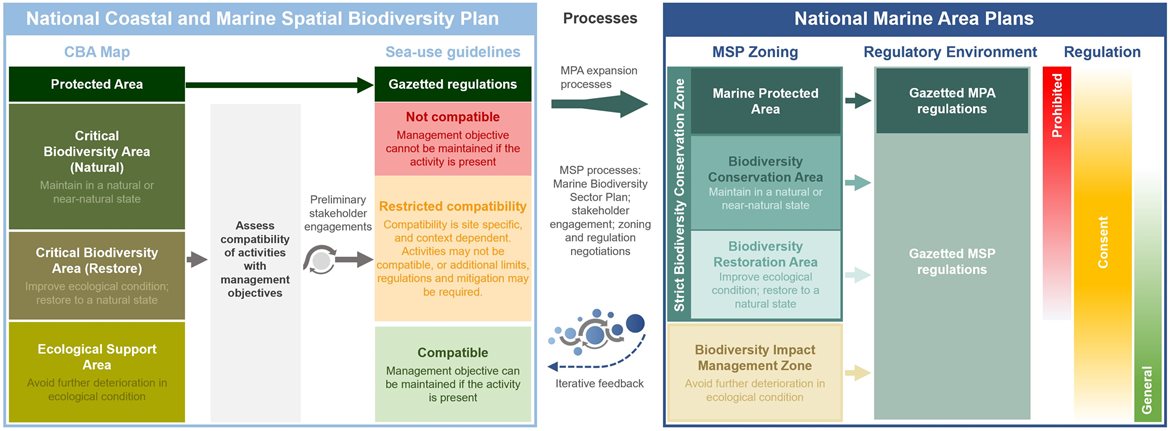

Based on the compatibility of sea-use activities with the management objective of each EBSA zone (see table below, from the sea-use guidelines of the National Coastal and Marine Spatial Biodiversity Plan), it is recommended for MSP that compatible activities are managed as General activities, which are those that are permitted and regulated by current general rules and legislation. Activities that are conditional are recommended to be managed as Consent activities, which are those that can continue in the zone subject to specific regulations and controls, e.g., to avoid unacceptable impacts on biodiversity features, or to avoid intensification or expansion of impact footprints of uses that are already occurring and where there are no realistic prospects of excluding these activities. Activities that are not compatible are recommended to be Prohibited, where such activities are not allowed or should not be allowed (which may be through industry-specific regulations) because they are incompatible with maintaining the biodiversity objectives of the zone. These recommendations are subject to stakeholder negotiation through the MSP process, recognizing that there will likely need to be significant compromises among sectors. It is emphasized, as noted above, that if activities that are not compatible with the respective EBSA zones are permitted, it would require alternative Biodiversity Conservation Zones or offsets to be identified. If this is not possible, it is recommended that the activity is Prohibited.

List of all sea-use activities, grouped by their Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) zones, and scored according to their compatibility with the management objective of the EBSA’s Biodiversity Conservation Zone (i.e., Critical Biodiversity Area, CBA) and Environmental Impact Management Zone (i.e., Ecological Support Area, ESA). Activity compatibility is given as Y = yes, compatible, C = conditional or N = not compatible, with major activities that are present in the EBSA shaded in grey.

There are also some pressures on biodiversity features within the EBSA that originate from activities outside of these EBSA or beyond the jurisdiction of MSP. In support of maintaining the ecological integrity of and benefits delivered by the key biodiversity features, these other activities need to be appropriately managed by complementary initiatives.

Recommendations for other activities beyond the jurisdiction of MSP management to support securing key biodiversity features within the EBSA.

[Top]

Proposed zonation of the EBSA, with the cumulative intensity footprint of activities within the EBSA (sorted highest to lowest) given relative to the national footprint of those activities to illustrate feasibility of management interventions.

Most of the activities in the EBSA relate to coastal (generally shore-based) biological resource use, including: oyster harvesting, abalone harvesting, subsistence harvesting, recreational shore angling, linefishing (commercial and recreational) and south coast rock lobster harvesting. All of these activities are recommended to continue in both EBSA zone as Consent activities. Inshore trawling and, to a lesser extent, offshore trawling are present in the EBSA; they are recommended to continue in the Impact Management Zone, but are incompatible activities with the Conservation Zone, where, after revised zoning, they currently do not exist and are recommended to be Prohibited. Squid fishing is an important activity in this EBSA and is recommended to continue as a Consent activity in both EBSA zones. Other fisheries present in the EBSA that comprise a small fraction of their respective national footprints include: benthic (hake) longlining, south coast rock lobster harvesting and small pelagics fishing, all of which are recommended to continue as Consent activities in both EBSA zones. Oil and gas (exploration and production) are also present in the EBSA, exclusively in the Impact Management Zone where it is recommended to continue as a Consent activity; because it currently does not occur in the Conservation Zone, it is recommended to be Prohibited from that zone. Some of the country’s ports and harbours also occur in the area but these are exclusively within the MPAs and thus are beyond the management recommendations of the EBSA zones. Shipping is recommended to continue under current general rules and legislation. Thus, in all cases, the EBSA zonation has no or minimal impact on the national footprint for the listed marine activities.

There are also several activities that are largely outside the EBSA but have downstream impacts to the biodiversity within the EBSA, e.g., from mean annual runoff reduction, coastal development, coastal disturbance, and wastewater discharge. The impacts should be managed, but principally fall outside the direct management and zoning of the EBSA. These existing activities are proposed as Consent activities for both EBSA zones, recognising that they should ideally be dealt with in complementary integrated coastal zone management in support of the EBSA. For example, investment in eradicating the alien invasive species could aid in improving the ecological condition of rocky and mixed shores, improving benefits for subsistence and recreational harvesting; and rehabilitation of degraded dunes and formalising access points could support improved habitat for nesting shorebirds, and enhanced benefits for coastal protection during storm surges. Similarly, improved estuary management through development of appropriate freshwater flow requirements, estuarine management plans and wastewater management regulations can improve the ecological condition of the surrounding marine environment, in turn, improving water quality and safe conditions for human recreation.

Management recommendations for MPAs

It is recommended that management is strengthened in the three existing MPAs (Tsitsikamma, Robberg and Goukamma MPAs) and adjacent land-based protected areas that cover some of the estuarine parts of Tsitskamma-Robberg. Potential MPA expansion within the EBSA should be explored to ensure that the features for which the EBSA was described receive adequate protection. See Future Process below for more details.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) in the Tsitsikamma-Robberg EBSA. Land-based protected areas are also shown (from DFFE, 2021).

[Top]

Management recommendations for MSP

Developing the biodiversity sector’s input to the national Marine Spatial Planning process

Following the initial management recommendations proposed for Tsitsikamma-Robberg, outlined above, South Africa iteratively developed a National Coastal and Marine Spatial Biodiversity Plan (NCMSBP; Harris et al. 2022a,b) that underpinned the Marine Biodiversity Sector Plan (DFFE 2022). The latter constitutes the biodiversity sector’s input into the national Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) process. The NCMSBP comprises a Map of Critical Biodiversity Areas and Ecological Support Areas (abbreviated to CBA Map), and a set of sea-use guidelines that indicate activity compatibility with the management objectives of each of the CBA Map categories. These two components form the basis for the proposed biodiversity zones and management recommendations for the Marine Area Plans. EBSAs are an integral part of the NCMSBP, and thus the Biodiversity Sector Plan. Therefore, these products informed the proposed zoning and sea-use guidelines for EBSAs in the MSP process.

Schematic diagram illustrating that the National Coastal and Marine Spatial Biodiversity Plan will inform the Marine Area Plans through the Marine Biodiversity Sector Plan (DFFE 2022), and will be iteratively updated and refined based on feedback. The process for deriving the sea-use guidelines is also shown, indicating that it is based on an assessment of activity compatibility with the management objective of Critical Biodiversity Area (CBA) Natural, CBA Restore and Ecological Support Areas (ESAs). Marine Protected Area (MPA) expansion, focussing on CBAs, will also take place in a separate but related process. The outcomes of the Marine Spatial Planning and MPA expansion processes will be incorporated into the Marine Area Plans and will be fed back into future updates of the National Coastal and Marine Spatial Biodiversity Plan.

[Top]

Proposed Zones

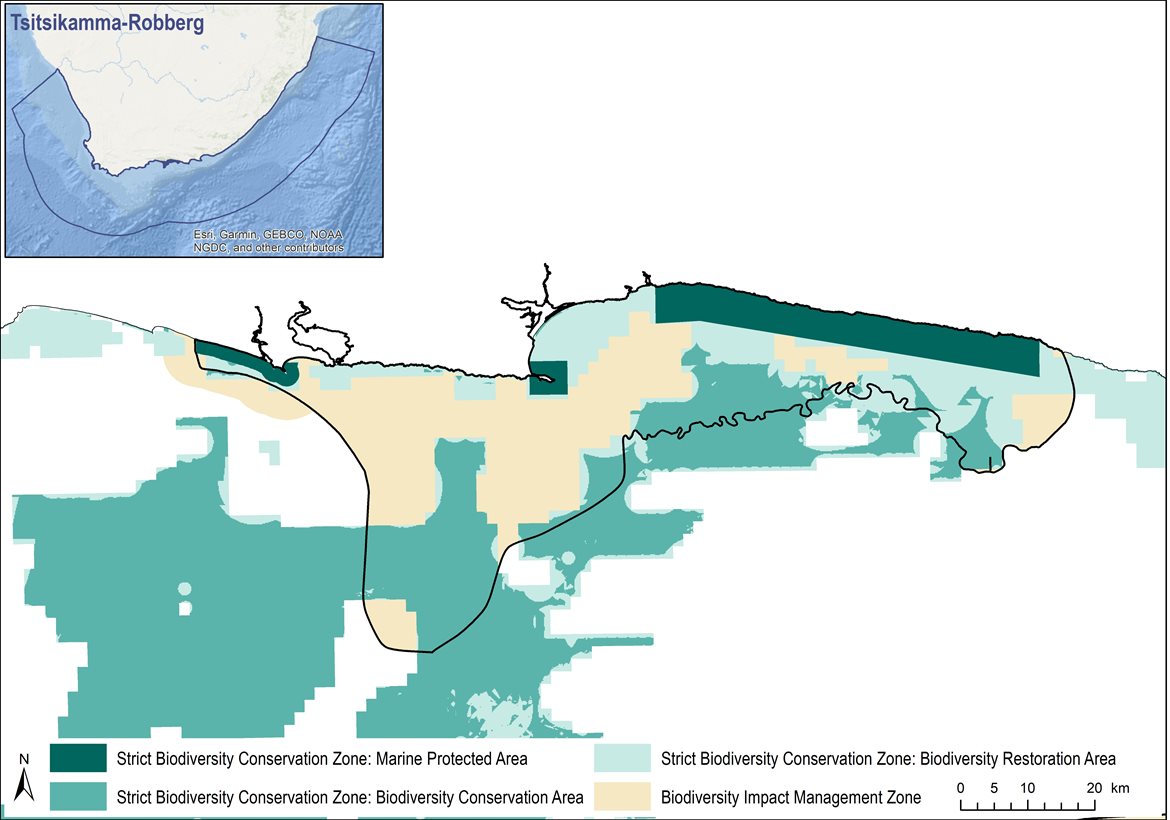

The proposed biodiversity zones for the EBSA in MSP comprises two types: a Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zone; and a Biodiversity Impact Management Zone. The former has three sub-categories: Marine Protected Area; Biodiversity Conservation Area; and Biodiversity Restoration Area. All of these zones and sub-categories are found in Tsitsikamma-Robberg.

The Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zone is primarily a Biodiversity Conservation Area, where the management objective of this zone is to maintain the sites in natural or near-natural ecological condition. The rest of the Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zone comprises a Biodiversity Restoration Area, where the management objective of the zone is to improve the ecological condition of the sites and, in the long term, restore them to a natural / near-natural state, or as near to that state as possible. As a minimum, avoid further deterioration in ecological condition and maintain options for future restoration. The rest of the EBSA is a Biodiversity Impact Management Zone. This is a multi-use area that may already be heavily impacted, but needs to be kept ecologically functional because it is still important for marine biodiversity patterns, ecological processes, and ecosystem services. Therefore, the management objective is to avoid further deterioration in ecological condition.

Proposed biodiversity zones for the Tsitsikamma-Robberg EBSA for South Africa’s Marine Area Plans. Land-based protected areas are not shown but do extend into some of the estuarine habitat (see previous section).

Proposed Sea-Use Guidelines

All sea-use activities were listed and evaluated according to their compatibility with the management objective of each of the proposed biodiversity zones. Where various aspects of an activity have a different impact on the environment, these were reflected separately, e.g., impacts from petroleum exploration are different to those from production. Activity compatibility was based largely on the ecosystem-pressure matrix from the NBA 2018 (Sink et al. 2019), which is a matrix of expert-based scores of the functional impact and recovery time for each activity on marine ecosystems (adapted from Halpern et al. 2007). Activities were then classified into those that are Compatible, Not Compatible or have Restricted Compatibility with the management objectives of each proposed biodiversity zone. This classification followed a set of predefined principles that account for the severity and extent of impact, similar to the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems criterion C3 (Keith et al. 2013). Some exceptions and adjustments were made based on initial discussions as part of the MSP process.

Sea-use guidelines for Tsitsikamma-Robberg. List of all sea-use activities, grouped by their broad sea use and Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) Zones, and categorised according to their compatibility with the management objective of Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zone: Biodiversity Conservation Area (SBCZ: BCA); Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zone: Biodiversity Restoration Area (SBCZ: BRA); and the Biodiversity Impact Management Zone (BIMZ). Activity compatibility is given as Y = yes, compatible, R = restricted compatibility, or N = not compatible. Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zone: Marine Protected Areas (SBCZ: MPA) are managed according to their gazetted regulations.

Proposed management recommendations for activities with each of the different compatibility ratings:

-

Compatible: Activities should be allowed and regulated by current general rules. Notwithstanding, there should still be duty of care, possibly requiring monitoring and evaluation programmes, to avoid unintended cumulative impacts to the biodiversity features for which this area is recognised.

-

Restricted compatibility: A robust site-specific, context-specific assessment is required to determine the activity compatibility depending on the biodiversity features for which the site was selected. Particularly careful attention would need to be paid in areas containing irreplaceable to near-irreplaceable features where the activity may be more appropriately evaluated as not permitted. The ecosystem types in which the activities take place may also be a consideration as to whether or not the activity should be permitted, for example. Where it is permitted to take place, strict regulations and controls over and above the current general rules and legislation would be required to be put in place to avoid unacceptable impacts on biodiversity features. Examples of such regulations and controls include: exclusions of activities in portions of the zone; avoiding intensification or expansion of current impact footprints; additional gear restrictions; and temporal closures of activities during sensitive periods for biodiversity features.

-

Not compatible: The activity should not be permitted to occur in this area because it is not compatible with the management objective. If it is considered to be permitted as part of compromises in MSP negotiations, it would require alternative Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zones and/or offsets to be identified. However, if this is not possible, it is recommended that the activity remains prohibited within the Strict Biodiversity Conservation Zone.

[Top]

Research Needs

There are no specific research needs for this EBSA in addition to those for all EBSAs.

Future Process

There needs to be full operationalisation and practical implementation of the proposed zoning in the national marine spatial plan, with gazetted management regulations following the proposed management recommendations outlined above. Possible MPA expansion within the EBSA should be explored, with relevant areas included into focus areas that can be considered further in a dedicated MPA expansion process with adequate and meaningful stakeholder engagement. Further alignment between land-based and marine biodiversity priorities should also be strengthened, e.g., through the cross-realm planning in the CoastWise project. This EBSA is also part of a World Heritage Site proposal that is being developed.

References

DFFE, 2021. South African Protected Areas Database (SAPAD). Available at: https://egis.environment.gov.za/protected_and_conservation_areas_database.

DFFE, 2022. Biodiversity Sector Plan: Input for Marine Spatial Planning (MSP). Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, Cape Town.

Halpern, B.S., Selkoe, K.A., Micheli, F., Kappel, C.V., 2007. Evaluating and Ranking the Vulnerability of Global Marine Ecosystems to Anthropogenic Threats. Conservation Biology 21, 1301–1315.

Harris, L.R., Holness, S.D., Kirkman, S.P., Sink, K.J., Majiedt, P., Driver, A., 2022. National Coastal and Marine Spatial Biodiversity Plan Version 1.2 (Released: 12-04-2022). Nelson Mandela University, Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, and South African National Biodiversity Institute, South Africa.

Harris, L.R., Holness, S.D., Kirkman, S.P., Sink, K.J., Majiedt, P., Driver, A., in review. A robust, systematic approach for developing the biodiversity sector’s input for multi-sector Marine Spatial Planning. Ocean & Coastal Management.

Keith, D.A., Rodríguez, J.P., Rodríguez-Clark, K.M., Nicholson, E., Aapala, K., Alonso, A., Asmussen, M., Bachman, S., Basset, A., Barrow, E.G., Benson, J.S., Bishop, M.J., Bonifacio, R., Brooks, T.M., Burgman, M.A., Comer, P., Comín, F.A., Essl, F., Faber-Langendoen, D., Fairweather, P.G., Holdaway, R.J., Jennings, M., Kingsford, R.T., Lester, R.E., Nally, R.M., McCarthy, M.A., Moat, J., Oliveira-Miranda, M.A., Pisanu, P., Poulin, B., Regan, T.J., Riecken, U., Spalding, M.D., Zambrano-Martínez, S., 2013. Scientific Foundations for an IUCN Red List of Ecosystems. PLoS ONE 8, e62111.

Sink, K.J., Holness, S., Skowno, A.L., Franken, M., Majiedt, P.A., Atkinson, L.J., Bernard, A., Dunga, L.V., Harris, L.R., Kirkman, S.P., Oosthuizen, A., Porter, S., Smit, K., Shannon, L., 2019. Chapter 7: Ecosystem Threat Status, In South African National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 Technical Report Volume 4: Marine Realm. eds K.J. Sink, M.G. van der Bank, P.A. Majiedt, L.R. Harris, L.J. Atkinson, S.P. Kirkman, N. Karenyi. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12143/6372.

[Top]